To many of us, his talent isn’t obvious. Too much noise always gets in the way. Ego. Insecurity. Immaturity. Neurosis. Some performers are empowered by their deficits; Jerry Lewis’ took him just so far, and then left him stranded and exposed, swooning in self-pity or foaming over persecution by an illusory cabal of envious insiders.

It wasn’t long

after the war and the advent of television. America was ready for a new clown.

And there he was, no Emmett Kelly, but somewhere between a schlemiel and a

schlimazel. Whatever, it worked pussycat, and together with his partner, Dean

Martin, he had the world at his feet. And then the ground began to tremble.

With few exceptions, most of his work has chaotic noise that cracks the fourth wall, through which he shrieks to the audience to appreciate his efforts, to applaud his genius, thereby sacrificing character for personal adulation. Jerry can’t seem to help it. He really wants you know, damn it, how f’n hard he’s sweating for your smiles. The self-loathing is palpable.

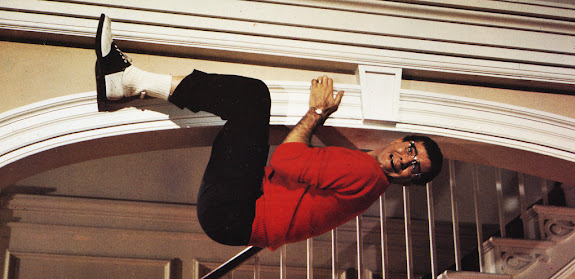

His talent was

one of daring invention, of wild kinetic energy, unregulated by taste or

refinement. He didn’t follow orders or regulations. He did it all himself.

Jerry Lewis had guts and stamina that pushed him to the front of the crowd –

but once there, he so easily followed the path of least resistance.

His style of

humor was destabilized as the 1960s progressed. Not even Vegas saved him. He

retreated into charities that eventually disowned him. Nowadays, his albums are

rarely played; his films, unwatched, whereas his boozy buddy, Deano, just keeps

burbling along.

Much of Jerry’s

humor had him portraying a man of inferior mental faculties. That hasn’t aged

well. It doesn’t matter because, in the end, it was all about Jerry anyway.

That’s the lesson, pussycat.

Jerry Lewis joins

the immortals with the wondrous, show-stopping breadth of his banality.